Author: Menios Constantinou

Photographer: All images used with permission.

Overloaded cupboard shelves, bending under the weight of old boxes filled with documents: faded photos and newspaper clippings, half-torn school report cards, dog-eared diaries and letters.

Amid the madness of the decluttering craze, such treasured items are being tossed out with reckless abandon.

But Noah Riseman, Professor of History at ACU’s National School of Arts and Humanities, believes there’s a good reason to hold onto these keepsakes.

“I think everyone potentially has items that may be of interest to historians and future generations,” says Professor Riseman, a Melbourne-based researcher who specialises in Indigenous and LGBTI history.

“Personal archives have traditionally been seen as idiosyncratic and only of value to the person who owns them. But there’s a new line of thought coming through which challenges that, and argues that personal archives can be of broader historical value.”

Riseman has witnessed this firsthand. His four-year research project Serving in Silence? uncovered the untold stories of 145 gay, lesbian and trans military personnel, and relied heavily on the private troves of those involved.

“The people we interviewed shared with us all types of documents: papers, letters, photographs, old news clippings and all sorts of stuff they saved in personal archives throughout their entire lives,” he says.

“In many cases, they saved records that we otherwise, as historians, wouldn’t have access to — documents we couldn’t get through official institutions.”

One of those interviewed for the LGBTI military history project was the former Royal Australia Air Force (RAAF) academy cadet Richard Gration, who had both a sharp memory and a trove of documents cataloguing his mistreatment.

Gration was one of four cadets accused of homosexual misconduct and interrogated under the Australian Defence Force’s longstanding ban on gay, lesbian and bisexual service personnel.

Their treatment during that investigation led to a court of inquiry — the only known case where the excesses of ADF investigators were officially rebuffed. But for some unknown reason, the record of that inquiry, held in March 1982, was never transferred to the National Archives.

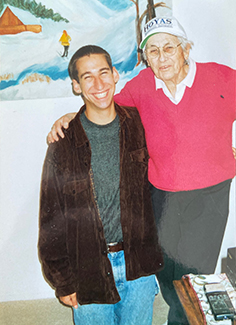

RAAF cadet Richard Gration.

It was only when Gration gave Riseman access to his personal archive that the inquiry document was exposed. Riseman requested the record and the ADF finally released it, making a redacted copy of the document publicly accessible through the National Archives for the first time.

“I don’t for one minute think it was a conspiracy or a conscious plot by the ADF to cover up this case,” Riseman says. “It’s just that the document wasn’t there, and because it wasn’t there, nobody knew to look for it.”

In this instance, he adds, it’s the power of the personal archive that helped to expose the institution’s past behaviour — and the silences in its official records.

In other words, if Gration had not kept a record of the case, the story of those air force cadets may never have come to light; or, at the very least, would have taken much longer to be exposed.

Riseman’s current research into transgender history also taps into the richness of personal archives, with a promise of bringing many more untold stories to the fore.

“One former activist I interviewed saved everything in her life going back to her childhood report card — and that included personal stuff, but also many documents and newspaper clippings from the early years of the organisation Transgender Victoria, where there’s very little paper trail anywhere else,” he says.

“This is just one example, but it shows there are people out there with stories to tell, who’ve kept these really rich personal archives that open up new lines of inquiry and reveal information that’s not kept anywhere else.”

Many years after the death of Noah Riseman’s grandmother, his mother made a surprise discovery.

“She uncovered this massive trove of things my grandmother had collected over the years — photographs and letters and diaries she had written that went back to 1950s — and it was really remarkable because it gave an insight into the inner psychology of this woman,” Riseman says.

Pictures found in Noah's grandmother's personal archive.

“When I look at these letters, to me they’re about my family, about my grandmother. But more broadly speaking, they tell us about a particular class and a particular religion of woman, in a particular era.

“They are significant to history beyond just our family, in that they tell us the story of the life of a Jewish woman, circa the 1950s, 60s and 70s in the United States… how they dealt with life and the pressures they faced.”

In a nation as diverse as Australia, there may be many more secret stories lying deep in the recesses of our clutter; stories about people who do not commonly feature in the history books.

“A lot of these groups that are not written in the official histories tend to be people from marginalised sections of society: the working class, Indigenous people, immigrants, women, LGBTI and all sorts of other people,” says Riseman, whose research explores the experiences of minority groups in modern Australia.

“Some people might have immigration stories and documents that are of interest, others might have stories about Indigenous struggles, or the welfare system, or even just about families and their histories and the way we understand things like class and ethnicity.

“Often personal archives and objects are the best ways we can get insights into how these people lived.”

So, does the trend towards decluttering — a movement that promises our lives will better without so-called “sentimental clutter” — spell danger for personal archives? Could it lead to the wholesale loss of treasures that might be of interest to future generations?

Possibly, yes. But there might also be a simple solution.

“I understand the reality that you can’t keep everything,” Riseman says. “But there are some digital tools out there that mean we can have it both ways.”

Free scanning apps like CamScanner or other similar software allow people to create digital versions of personal documents, using a smartphone or a tablet.

“It’s a brilliant app that has revolutionised how historians do history and archival research,” says Riseman, “and it means that anyone can preserve documents without having to hold on to everything physically, so we eliminate some of the paper trail.”

In the end, however, some will always opt for the physical item over a digital version.

“Archivists talk about how we tend to save stuff that's important to us for some reason or another, and it might be that we are trying to identify ourselves within a bigger story,” Riseman says.

“When I think of the transgender people I’ve interviewed, I would say they kept these personal archives as a way of reminding them that they weren’t alone; that there were others out there, going through the same sorts of struggles.”

Noah Riseman is a Professor of History at ACU’s National School of Arts and Humanities in Melbourne. He is currently working on his ARC Discovery Project, Transgender Australians: The History of an Identity. For enquiries, email Noah.Riseman@acu.edu.au. You can order his book Serving in Silence? online.

We're available 9am–5pm AEDT,

Monday to Friday

If you’ve got a question, our AskACU team has you covered. You can search FAQs, text us, email, live chat, call – whatever works for you.